Automatic differentiation and dual numbers in C++ are pretty neat, with a single exception

To cut down on clickbait, the exception is the lack of an overloadable ternary operator in C++

What is automatic differentiation anyway?

The basic premise for what we’re trying to do today is to take an arbitrary function that does some maths on one or more inputs, and returns one or more results. We then want to differentiate that function with respect to one of its inputs. That is to say, given something like:

float my_func(float x);

We want to get the derivative with respect to x. This function could be a more complicated, eg:

std::array<float, 6> my_func(float x, float y, float cst);

and we may want to get the derivatives of any of the outputs with respect to any of the inputs

Differentiation revisited

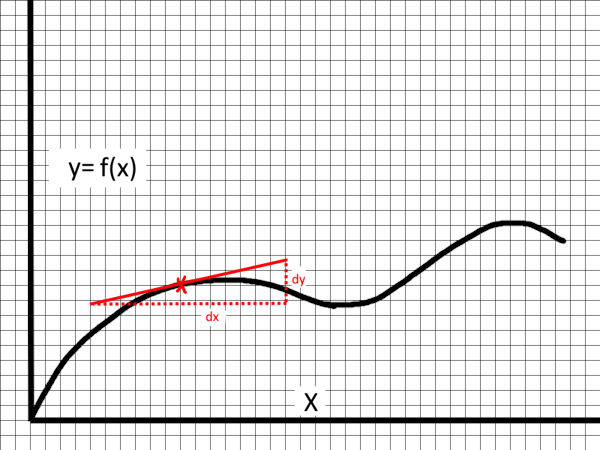

If you’re willing to dredge up some maths, you might remember that differentiation is the process of taking a function

y = f(x)

And differentiating it to get its derivative - the derivative being the rate of change of a function with respect to some variable

dy/dx = f'(x)

Taking the slope of line which is tangent to a point on a function gives you the rate of change

As a brief refresher for everyone who isn’t a maths nerd, there are a lot of simple functions that we can differentiate by hand, like so

| Function (ie we set f(x) to this) | Derivative with respect to x | Note |

|---|---|---|

| f(x) | f’(x) | |

| f’(x) | f’‘(x) | |

| x | 1 | |

| x^2 | 2x | |

| 2x^3 | 6 x^2 | |

| sin(x) | cos(x) | |

| e^x | e^x | |

| f(y) + f(x) | f’(x) | f(y) is treated like a constant, as we’re differentiating with respect to x only |

| f(x, y) | f^(1, 0)(x, y) | This notation means differentiate only in the x direction |

| f(g(x)) | f’(g(x)) g’(x) | (aka the chain rule) |

| f(x) g(x) | f(x) g’(x) + f’(x) g(x) | (aka the product rule) |

For every particular kind of operation, there’s a specific rule for differentiating it. You might remember that the general rule for differentiating things of the form ax^n is nax^(n-1), or that sin(x) -> cos(x). Or if you have f(x) + g(x), you can simply add the derivatives together, to get f'(x) + g'(x). Great!

Differentiation is a very mechanistic process. While simple equations are easy enough to do by hand, a recent strain of self inflicted brain damage compelled me to differentiate this:

function double_kerr_alt(t, p, phi, z)

{

var i = CMath.i;

$cfg.R.$default = 4;

$cfg.M.$default = 0.3;

$cfg.q.$default = 0.2;

var R = $cfg.R;

var M = $cfg.M;

var q = $cfg.q;

var sigma = CMath.sqrt(M*M - q*q * (1 - (4 * M * M * (R * R - 4 * M * M + 4 * q * q)) / CMath.pow(R * (R + 2 * M) + 4 * q * q, 2)));

var r1 = CMath.sqrt(p*p + CMath.pow(z - R/2 - sigma, 2));

var r2 = CMath.sqrt(p*p + CMath.pow(z - R/2 + sigma, 2));

var r3 = CMath.sqrt(p*p + CMath.pow(z + R/2 - sigma, 2));

var r4 = CMath.sqrt(p*p + CMath.pow(z + R/2 + sigma, 2));

var littled = 2 * M * q * (R * R - 4 * M * M + 4 * q * q) / (R * (R + 2 * M) + 4 * q * q);

var pp = 2 * (M*M - q*q) - (R + 2 * M) * sigma + M * R + i * (q * (R - 2 * sigma) + littled);

var pn = 2 * (M*M - q*q) - (R - 2 * M) * sigma - M * R + i * (q * (R - 2 * sigma) - littled);

var sp = 2 * (M*M - q*q) + (R - 2 * M) * sigma - M * R + i * (q * (R + 2 * sigma) - littled);

var sn = 2 * (M*M - q*q) + (R + 2 * M) * sigma + M * R + i * (q * (R + 2 * sigma) + littled);

var k0 = (R * R - 4 * sigma * sigma) * ((R * R - 4 * M * M) * (M * M - sigma * sigma) + 4 * q * q * q * q + 4 * M * q * littled);

var kp = R + 2 * (sigma + 2 * i * q);

var kn = R - 2 * (sigma + 2 * i * q);

var delta = 4 * sigma * sigma * (pp * pn * sp * sn * r1 * r2 + CMath.conjugate(pp) * CMath.conjugate(pn) * CMath.conjugate(sp) * CMath.conjugate(sn) * r3 * r4)

-R * R * (CMath.conjugate(pp) * CMath.conjugate(pn) * sp * sn * r1 * r3 + pp * pn * CMath.conjugate(sp) * CMath.conjugate(sn) * r2 * r4)

+(R * R - 4 * sigma * sigma) * (CMath.conjugate(pp) * pn * CMath.conjugate(sp) * sn * r1 * r4 + pp * CMath.conjugate(pn) * sp * CMath.conjugate(sn) * r2 * r3);

var gamma = -2 * i * sigma * R * ((R - 2 * sigma) * CMath.Imaginary(pp * CMath.conjugate(pn)) * (sp * sn * r1 - CMath.conjugate(sp) * CMath.conjugate(sn) * r4) + (R + 2 * sigma) * CMath.Imaginary(sp * CMath.conjugate(sn)) * (pp * pn * r2 - CMath.conjugate(pp) * CMath.conjugate(pn) * r3));

var G = 4 * sigma * sigma * ((R - 2 * i * q) * pp * pn * sp * sn * r1 * r2 - (R + 2 * i * q) * CMath.conjugate(pp) * CMath.conjugate(pn) * CMath.conjugate(sp) * CMath.conjugate(sn) * r3 * r4)

-2 * R * R * ((sigma - i * q) * CMath.conjugate(pp) * CMath.conjugate(pn) * sp * sn * r1 * r3 - (sigma + i * q) * pp * pn * CMath.conjugate(sp) * CMath.conjugate(sn) * r2 * r4)

- 2 * i * q * (R * R - 4 * sigma * sigma) * CMath.Real(pp * CMath.conjugate(pn) * sp * CMath.conjugate(sn)) * (r1 * r4 + r2 * r3)

- i * sigma * R * ((R - 2 * sigma) * CMath.Imaginary(pp * CMath.conjugate(pn)) * (CMath.conjugate(kp) * sp * sn * r1 + kp * CMath.conjugate(sp) * CMath.conjugate(sn) * r4)

+ (R + 2 * sigma) * CMath.Imaginary(sp * CMath.conjugate(sn)) * (kn * pp * pn * r2 + CMath.conjugate(kn) * CMath.conjugate(pp) * CMath.conjugate(pn) * r3));

var w = 2 * CMath.Imaginary((delta - gamma) * (z * CMath.conjugate(gamma) + CMath.conjugate(G))) / (CMath.self_conjugate_multiply(delta) - CMath.self_conjugate_multiply(gamma));

var e2y = (CMath.self_conjugate_multiply(delta) - CMath.self_conjugate_multiply(gamma)) / (256 * sigma * sigma * sigma * sigma * R * R * R * R * k0 * k0 * r1 * r2 * r3 * r4);

var f = (CMath.self_conjugate_multiply(delta) - CMath.self_conjugate_multiply(gamma)) / CMath.Real((delta - gamma) * (CMath.conjugate(delta) - CMath.conjugate(gamma)));

var dp = (e2y / f);

var dz = e2y / f;

var dphi_1 = p * p / f;

var dt = -f;

var dphi_2 = -f * w * w;

var dt_dphi = f * 2 * w;

var ret = [];

ret.length = 16;

ret[0 * 4 + 0] = dt;

ret[1 * 4 + 1] = dp;

ret[2 * 4 + 2] = dphi_1 + dphi_2;

ret[3 * 4 + 3] = dz;

ret[0 * 4 + 2] = dt_dphi * 0.5;

ret[2 * 4 + 0] = dt_dphi * 0.5;

return ret;

}

(sometimes I think technology was a mistake)

Which also involves differentiating complex numbers. This is slightly tricky to do by hand, so automating it is helpful. Today we’re looking at automatic differentiation, but numerical differentiation1 is also a very widely used technique

Dual numbers

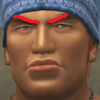

The foundation for automatic differentiation is often started at a concept called dual numbers. As an analogy, if you remember your complex maths, you might remember that

i = sqrt(-1), and i^2 = -1

Complex numbers exist in the form a + bi with a and b being real numbers, and i is the imaginary unit

Dual numbers are similar, except instead of i you have ε, and the rule that ε follows is:

ε != 0, and ε^2 = 0

This slightly odd definition forms a system called the dual numbers. Operations on dual numbers still obey all the other usual rules of maths that you’d expect from real numbers (and 2d vectors), such as the following:

(a + bε) + (c + dε) = (a + c) + (b + d)ε

(a + bε) - (c + dε) = (a - c) + (b - d)ε

(a + bε) * (c + dε) = ac + bdε^2 + adε + bcε (then group the terms and apply ε^2 = 0) = ac + (ad + bc)ε

(a + bε)^2 = a^2 + 2abε + bε^2 = a^2 + 2abε

(a + bε)^n = a^n + n a^(n-1) bε + (n choose 2) a^(n-2) b^2 ε^2 ... (all higher powers of ε are set to 0) = a^n + n a^(n-1) bε

Dual numbers have the key property that if you construct a dual number f(x) + f'(x)ε, the ε term is always the derivative of the real term no matter what series of operations you run it through. This makes them extremely useful for differentiating equations

For example, if you want to know the derivative of x^3, you write

f(x) = x^3

f(a + bε) = (a + bε)^3 ->

expand:

= a^3 + 3a^2b ε + 3ab^2 ε^2 + b^3 ε^3 ->

set all terms of ε^2 and higher to 0:

= a^3 + 3a^2b ε

Substitute in a = x, b = the derivative of x = 1:

= x^3 + 3x^2 ε

You can read off the real part as x^3, which unsurprisingly is the result of applying ^3 to x, and the derivative from the dual part: 3x^2, which matches with what you’d expect from differentiating x^3. One other thing to note is that unlike imaginary numbers, the non-real part of a dual number cannot influence the real part in any way

Here’s a table of basic operations:

| Operation | Result |

| (a + bε) + (c + dε) | (a + c) + (b + d)ε |

| (a + bε) - (c + dε) | (a - c) + (b - d)ε |

| (a + bε) * (c + dε) | ac + (ad + bc)ε |

| (a + bε) / (c + dε) | a/c + ((bc - ad) / c^2) ε |

| (a + bε)^n | a^n + (n a^(n-1) b) ε |

| (a + bε)^(c + dε) | a^c + (a^c) ((b c / a) + d log(a)) ε |

| log(a + bε) | log(a) + b/a ε |

| |a + bε| | |a| + (a b / |a|)ε, aka sign(a) * bε |

| e^(a + bε) | e^a + b e^a ε |

| sin(a + bε) | sin(a) + b cos(a) ε |

| cos(a + be) | cos(a) - b sin(a) ε |

| tan(a + be) | tan(a) + b / (cos(a))^2 ε |

| sinh(a + be) | sinh(a) + b cosh(a) ε |

| cosh(a + be) | cosh(a) + b sinh(a) ε |

| tanh(a + be) | tanh(a) + b (1 - (tanh(a))^2 ε |

| asin(a + bε) | asin(a) + (b / sqrt(1 - a^2)) ε |

| acos(a + bε) | acos(a) - (b / sqrt(1 - a^2)) ε |

| atan(a + bε) | atan(a) - (b / (1 + a^2)) ε |

| atan2(a + bε, c + dε) | atan2(a, c) + ((bc - ad) / (c^2 + a^2)) ε |

| w0(a + bε) [lamberts w02] | w0(a) + (b w0(a) / (a w0(a) + a)) ε |

| a % b | it depends |

| a < b | a < b (ignore the derivatives when evaluating conditionals) |

| max(a, b) | people will argue about this a lot |

Numerical Accuracy

As a sidebar, while these derivatives are derived fairly straightforwardly, they can suffer from numerical accuracy problems. Herbie is a tremendously cool tool that can be used to automatically produce more accurate results that I use all the time, and people should be more aware of it. Here are some notable ones:

| Operation | Result |

| (a + bε) / (c + dε) | a/c + (b - a * d / c) / c ε |

| (a + bε)^(c + dε) | a^c + ((a^(c-1)) cb + (a^(c-1)) a log(a) d) ε |

| atan2(a + bε, c + dε) | atan2(a, c) + ((bc - ad) / hypot(c, a)) / hypot(c, a) ε |

Note that these expressions should be implemented exactly as written, because the order of floating point operations can matter

Code

struct dual

Some problems I find intractable in the abstract, so lets go through the skeleton of a concrete implementation of dual numbers. Code wise the representation of a dual number is pretty straightforward:

namespace dual_type

{

template<typename T>

struct dual

{

T real = {};

T derivative = {};

dual(){}

dual(T _real) : real(std::move(_real)){}

dual(T _real, T _derivative) : real(std::move(_real)), derivative(std::move(_derivative)){}

};

}

operator overloading

Implementing the operators that you need is also straightforward:

//...within struct dual, use the hidden friend idiom

friend dual<T> operator+(const dual<T>& v1, const dual<T>& v2) {

return dual(v1.real + v2.real, v1.derivative + v2.derivative);

}

friend dual<T> operator-(const dual<T>& v1, const dual<T>& v2) {

return dual(v1.real - v2.real, v1.derivative - v2.derivative);

}

friend dual<T> operator*(const dual<T>& v1, const dual<T>& v2) {

return dual(v1.real * v2.real, v1.real * v2.derivative + v2.real * v1.derivative);

}

friend dual<T> operator/(const dual<T>& v1, const dual<T>& v2) {

return dual(v1.real / v2.real, ((v1.derivative * v2.real - v1.real * v2.derivative) / (v2.real * v2.real)));

}

friend dual<T> operator-(const dual<T>& v1) {

return dual(-v1.real, -v1.derivative);

}

friend bool operator<(const dual<T>& v1, const dual<T>& v2) {

return v1.real < v2.real;

}

//etc etc

Free functions

namespace dual_type {

//relies on adl

//unfortunately, because C++ std::sin and friends aren't constexpr until c++26, you can't make this constexpr *yet*

template<typename T>

inline

dual<T> sin(const dual<T>& in)

{

return dual<T>(sin(in.real), in.derivative * cos(in.real));

}

template<typename T>

inline

dual<T> atan2(const dual<T>& v1, const dual<T>& v2) {

return dual(atan2(v1.real, v2.real), (v1.derivative * v2.real - v1.real * v2.derivative) / (v2.real * v2.real + v1.real * v1.real));

}

template<typename T>

inline

dual<T> lambert_w0(const dual<T>& v1)

{

return dual<T>(lambert_w0(v1.real), v1.derivative * lambert_w0(v1.real) / (v1.real * lambert_w0(v1.real) + v1.real));

}

//etc

}

Example

At this point, we have the pretty basic skeleton of a classic value replacement type in C++, which you can use like this:

template<typename T>

T some_function(const T& in)

{

return 2 * in * in + in;

}

int main()

{

//gives 10

float my_val = some_function(2.f);

//differentiate

dual<float> my_dual = some_function(dual<float>(2.f, 1.f));

//my_dual.real is 10, my_dual.derivative is 9

}

In general, a dual(value, 1) means to differentiate with respect to that value, and a dual(value, 0) means to treat that value as a constant

Complications

Lets look at some things we’ve left off so far

- %, branching, and min/max

- Mixed derivatives

- Higher order derivatives

- Complex numbers

- Post hoc differentiation

1.1 operator%

There are two useful ways to look at the derivative of the modulo function

- The derivative of

x % nisx', except for wherex % n == 0where it is undefined - The derivative of

x % nisx'

Which one is more useful is up to the problem you’re trying to solve, but I tend to go for the second. I mainly use this differentiator in general relativity, and this can be a useful definition there

It might seem incorrect on the face of it, but consider polar coordinates - if you have a coordinate (r, theta), the derivative is usefully defined everywhere as (dr, dtheta). Polar coordinates are inherently periodic in the angular coordinate, which is to say that theta -> theta % 2 PI, but you can still correctly assign a derivative dr, dtheta at the coordinate (r, 0) or (r, 2pi), or (r, 4pi)

Defining precisely what I mean by derivatives here is slightly beyond me, but I suspect that the kind of object we’re talking about is different. Coordinate systems in GR must be smooth, which means that theta actually has the range [-inf, +inf], and you fold the coordinate in on itself by ‘identifying’ theta with theta + 2PI, thus forming some kind of folded smooth topological nightmare. More discussions around this kind of coordinate system fun are reserved for the future - when weirdly enough it becomes a key issue in correctly rendering time travel

1.2 Branches and piecewise functions

Its common to implement branches, min, and max, as something like the following

template<typename T>

dual<T> min(const dual<T>& v1, const dual<T>& v2) {

if(v1.real < v2.real)

return v1;

else

return v2;

}

This similarly suffers from a similar issue as %, though more severely. The issue is that in any function which branches (or is a non smooth piecewise function), at the branch point there will exist a discontinuity, as min is not a smooth function. How severe this is for your particular problem varies. If you need smooth derivatives, you could define a transition bound between the two, or otherwise rework your min as some kind of soft, smoothed min

If you run into this problem, you’re probably already aware that these functions are not smooth - differentiating them via dual numbers like this doesn’t introduce any new problems, but it does mean that automatic differentiation isn’t quite a plug and play process if you’re differentiating code outside of your control

2. Mixed derivatives

Lets imagine you have a function f(x, y), and you want to differentiate this with dual numbers. The traditional way to do this is to say

f(x, y) dx

For the x direction, and

f(x, y) dy for the y direction. In dual numbers this is

f(a + bε, c + dε), with a = x, b = x', c = y, d = 0

for the x direction, and

f(a + bε, c + dε), with a = x, b = 0, c = y, d = y'

for the y direction. This isn’t surprising so far. This is an operation that involves independently differentiating your function twice - is there a way to do better?

Answer: Yes. Lets branch out our dual number system a bit, and introduce two new ε variables, called εx and εy

These two new variables have the following properties

εx^2 = 0

εy^2 = 0

εx εy = 0

With this new definition, we can now differentiate in two directions simultaneously:

f(a + bεx, c + dεy) with a = x, b = x', c = y, d = y'

The reason this works is because εx and εy are treated completely separately, and it is equivalent to doing the differentiation twice. The main advantage with this method is that you only evaluate the real part of your equation once, instead of twice - the disadvantage is that its more complicated to implement

3. Higher derivatives

Given that dual numbers give us the power to automatically differentiate things, the obvious approach for higher order derivatives is to use dual numbers on the dual numbers that we already have, to differentiate our derivatives. Less confusingly, what we’re trying to say is that if we want to differentiate

f(x)

To get

f'(x)

We make the substitution

f(a + bε)

to get our derivative f'(x)

To differentiate our derivative, clearly we do

f'(c + dε)

to get f''(x). Neat, but can you do this all at once?

The answer is: yes. It turns out that its very straightforward: to get a 3rd derivative, you simply change the initial rule. Instead of ε^2 = 0, you set ε^3 (and higher) = 0, and end up with a higher order dual number of the form

a + bε + cε^2, aka f(x) + f'(x) ε + f''(x) ε^2

4. Complex numbers

There’s very little information about this online, but there’s nothing special about mixing complex numbers with dual numbers. You can simply do:

complex<dual<float>> my_complex_dual

And you’ll be able to get the derivatives of the real and imaginary components as you’d expect. Because this layering is symmetric, you can also do:

dual<complex<float>> my_complex_dual;

Though this works great, its a bit more convoluted as your dual type needs to now be aware of operations that are generally only applied to complex numbers, like conjugation. Unfortunately, std::complex has very unfortunate behaviour in the former case, so if your complex type is std::complex, stick to the latter

Sidebar: std::complex is completely unusable here

Do be aware in the first case: C++ does not usefully allow custom types (or ints) to be plugged into std::complex: the result of doing so is unspecified and may not compile - and is possibly even undefined depending on the type. Even if std::complex<your_type> compiles, there’s no guarantee that functions like std::sqrt will compile (or work). This isn’t just a theoretical issue, as std::sqrt will unfortunately not compile in practice for types like value<T> that are discussed later. In general, std::complex is something you should strictly avoid anyway, as its specification is complete madness. For example, until C++26 the only way to access the real or imaginary parts by reference is:

reinterpret_cast<T(&)[2]>(z)[0] and reinterpret_cast<T(&)[2]>(z)[1]

I rate this: Oof/c++23

5. Post hoc differentiation

Its often necessary to build a tree of your expressions, that can be re-evaluated at a later date - eg for reverse differentiation3, or if you want to run forwards differentiation multiple times. The resulting AST can also then be used to generate code, which is very useful for high performance differentiation. In practice, its very rare that I ever use dual numbers directly on concrete values, but instead output the AST and derivatives of that AST as code - because the resulting code gets evaluated billions of times

Code

The basic gist for building a node base AST type here is something that looks like this:

namespace op {

enum type {

NONE,

VALUE,

PLUS,

MINUS,

UMINUS,

MULTIPLY,

DIVIDE,

SIN,

COS,

TAN,

LAMBERT_W0,

//etc

};

}

template<typename Func, typename... Ts>

auto change_variant_type(Func&& f, std::variant<Ts...> in)

{

return std::variant<decltype(f(Ts()))...>();

}

struct value_base

{

std::variant<double, float, int> concrete;

std::vector<value_base> args;

op::type type = op::NONE;

std::string name; //so that variables can be identified later. Clunky!

template<typename Tf, typename U>

auto replay_impl(Tf&& type_factory, U&& handle_value) -> decltype(change_variant_type(type_factory, concrete))

{

if(type == op::type::VALUE)

return handle_value(*this);

using namespace std; //necessary for lookup

using result_t = decltype(change_variant_type(type_factory, concrete));

if(args.size() == 1)

{

auto c1 = args[0].replay_impl(type_factory, handle_value);

return std::visit([&](auto&& v1)

{

if(type == op::UMINUS)

return result_t(-v1);

if(type == op::SIN)

return result_t(sin(v1));

assert(false);

}, c1);

}

if(args.size() == 2)

{

auto c1 = args[0].replay_impl(type_factory, handle_value);

auto c2 = args[1].replay_impl(type_factory, handle_value);

return std::visit([&](auto&& v1, auto&& v2) {

if constexpr(std::is_same_v<decltype(v1), decltype(v2)>)

{

if(type == op::PLUS)

return result_t(v1 + v2);

if(type == op::MULTIPLY)

return result_t(v1 * v2);

}

assert(false);

return result_t();

}, c1, c2);

}

assert(false);

}

};

template<typename T>

struct value : value_base {

value() {

value_base::type = op::VALUE;

value_base::concrete = T{};

}

value(T t) {

value_base::type = op::VALUE;

value_base::concrete = t;

}

friend value<T> operator+(const value<T>& v1, const value<T>& v2) {

value<T> result;

result.type = op::PLUS;

result.args = {v1, v2};

return result;

}

friend value<T> operator*(const value<T>& v1, const value<T>& v2) {

value<T> result;

result.type = op::MULTIPLY;

result.args = {v1, v2};

return result;

}

/*more operators, functions etc*/

template<typename Tf, typename U>

auto replay(Tf&& type_factory, U&& handle_value) -> decltype(type_factory(T()))

{

using result_t = decltype(type_factory(T()));

return std::get<result_t>(replay_impl(type_factory, handle_value));

}

};

template<typename T>

T my_func(const T& x)

{

T v1 = x;

T v2 = 2;

return v1 * v1 * v2 + v1;

}

int main() {

value<float> x = 2;

x.name = "x";

value<float> result = my_func(x);

dual<float> as_dual = result.replay([](auto&& in)

{

return dual(in);

},

[](const value_base& base)

{

if(base.name == "x")

return dual(std::get<float>(base.concrete), 1.f);

else

return dual(std::get<float>(base.concrete), 0.f);

});

//our function is x * x * 2 + x

//our real part is therefore 2*2*2 + 2 = 10

//our derivative is D(2x^2 + x), which gives 4x + 1

//which gives 9

std::cout << as_dual.real << " " << as_dual.derivative << std::endl;

}

Phew. The idea here is that each node in your AST contains a type (either a literal value, or a placeholder), and a series of arguments which themselves can be of any type. Its key to note that the external type T of a value<T> here is not used when replaying the contents of the tree, other than to get the final concrete result type. When replaying a statement, the stored std::variant<double, float, int> is transformed in a fashion determined by the type_factory function to a std::variant<dual<double>, dual<float>, dual<int>>, and handle_value is used to determine how values contained within value_base are promoted to your wrapping type (here, dual)

There are some tweaks that could be made here (handle_value taking a value_base instead of a T is a bit suspect, and I suspect this needs a liberal dollop of std::forward), but the basic structure should be decent to hang improvements off of

This avoids a lot of the mistakes I made when first writing a type of this kind, namely that your expression tree can contain multiple types in it, and that the type T is ignored. Its important to appreciate here that with some more work, what we’ve actually created is a simple functional programming language within C++, which can be used to do some very interesting things. Combining this with dual numbers will be extremely foundational for future articles, when I trick everyone into learning general relativity

If we could overload the ternary operator, this would be a lot better

This kind of basic functional language can be used to implement lots of things, including entire simulations of general relativity, opening up the door to all kinds of neat things when we eventually port this to generate code for the GPU. Eventually you’ll want side effects down the line, but you can get very far without them

The one very annoying thing is that C++ does not let you write this in a standard way, in any form:

value<T> my_value_1 = 0;

value<T> my_value_2 = 1;

value<T> my_value_3 = 2;

value<T> my_value_4 = 3;

value<T> my_value_3 = (my_value_1 < my_value_2) ? my_value_3 : my_value_4;

While there are questions around when a statement is evaluated, what C++ could really add that would be of significant help is a std::select. Numerical toolkits like eigen, DSLs that build up an AST like Z3, or vector/simd libraries often need a function that looks something like this:

template<typename T, typename U>

T select(T a, T b, U c) {

return c ? b : a;

}

Which, despite what I would consider to be a slightly suspect definition, forms a basis for building eagerly evaluated branches with a result that could be embedded in a tree easily (or used on SIMD operations). C++ could very much do with an overloadable std::select that is a customisation point (or an expression based if like Rust). Toolkits and libraries which operate on ASTs run into this frequently - as there’s no universally agreed on spelling for this function. Moreso, while the standard library imposes constraints on what types work in what functions, many functions rely on being able to apply true branches to your types - which means that they can never work with these AST types. Annoying!

The End

That’s it for this article, hopefully this is a useful reference for dealing with automatic differentiation in C++ in a concrete fashion. Next up we’ll see how this kind of differentiable programming is useful for rendering black holes, and generating high performance code that runs on the GPU! For an example of this in practice, check out my free tool for rendering general relativistic objects in realtime on the GPU

-

Sidebar: Numerical derivatives

While today we’ve been looking at analytic derivatives, it may be worth evaluating whether or not your problem is solvable via numerical derivatives. Briefly:

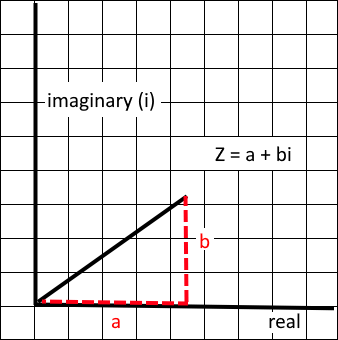

f'(x) ~= (f(x+h) - f(x)) / hThis is pretty straightforward to deduce by looking at a function on a graph

Where calculating the slope of the line recovers the above formula

In practice you very rarely use this specific definition of numerical derivatives as it is unstable, and you use a centered derivative, such as

f'(x) ~= (f(x + h) - f(x - h)) / 2hWhich gives much more stable results. This can be directly applied to a function to differentiate it, without the complexity of implementing automatic differentiation. Numerical differentiation will be the subject of future articles ↩

-

lambert_w0?

This function was a gigantic pain to find a viable implementation for when I needed it, so here it is in full. It’ll likely crop up in a future article, when we’re knee deep in general relativity together

template<typename T, int Iterations = 2> inline T lambert_w0(T x) { if(x < -(1 / M_E)) x = -(1 / M_E); T current = 0; for(int i=0; i < Iterations; i++) { T cexp = std::exp(current); T denom = cexp * (current + 1) - ((current + 2) * (current * cexp - x) / (2 * current + 2)); current = current - ((current * cexp - x) / denom); } return current; } -

Sidebar: Reverse/backwards automatic differentiation

While the main topic of this article is forward differentiation, reverse differentiation is worth a mention too. In forwards differentiation, you start at the roots of a tree, and may build towards several results from those roots. In reverse differentiation, we start at the end with those results, and walk up the tree towards our roots

Reverse differentiation works quite differently. You start off by setting a concrete value for our end derivative at the output, and then start differentiating backwards. With forward mode differentiation, at each step you carry forwards concrete values for all the derivatives, eg

a + bεx + cεy + dεzWhich means 4 calculations are being done in parallel. With reverse mode differentiation, as you walk up the graph, only one value is calculated - which is the the derivatives of the functions with respect to each other

In reverse differentiation, the expectation is that you’ve already done one forward pass over the graph when building it, so that you’re dealing with a tree of concrete values. This means that at each node in our graph, no matter how many variables you’re differentiating against, you only have a singular value that you’re propagating (instead of N values in forwards differentiation), right up until you hit the roots of our graph. The tradeoff is that you have to evaluate the graph multiple times if you have multiple outputs, which can result in it being less efficient than forward differentiation when there are lots of outputs

For arbitrary unstructured problems, some mix of forwards and backwards differentiation is likely the most efficient, as the specific efficiencies are dependent on the structure of your graph. This article is secretly the ground work for teaching people about general relativity, where forward differentiation is generally most efficient (you always have more outputs than inputs), so a more in depth discussion of backwards differentiation is intentionally left out - check out this article for an interesting in depth dive complete with code ↩